Sneak Peak

Preview

Chapter One

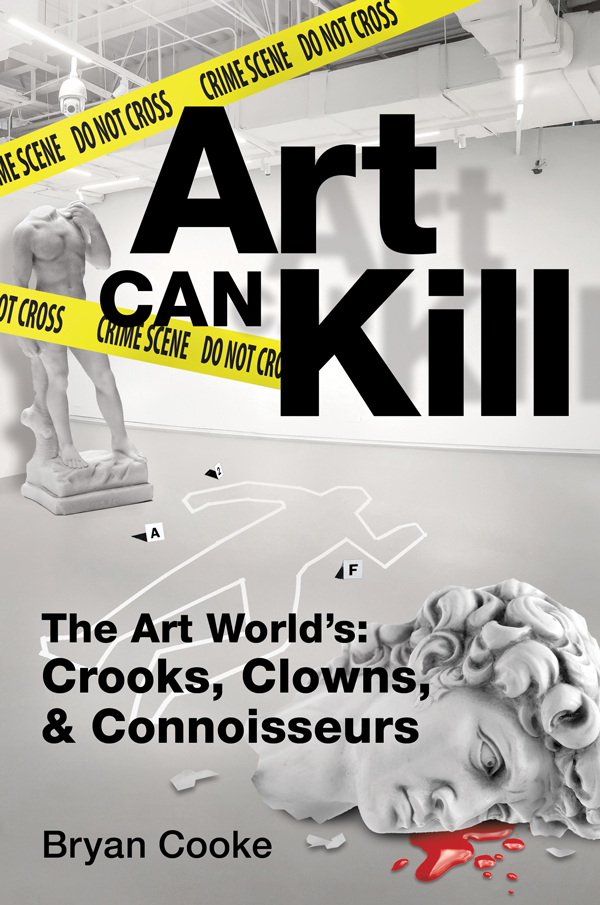

Art Can Kill

In 1984, Marcia Weisman breathlessly called to tell me that she had just purchased “a masterpiece by Richard Serra” from Larry Gagosian in New York. At the time, Marcia was campaigning to establish the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. She and her husband Frederick had one of LA’s notable collections of modern art. This new piece would be the grandest of the lot. She wanted me to take care of the shipping and installation arrangements.

“Call Larry!” she said. “He will tell you where to go get it.”

Gagosian told me the Corten steel structure measured eight feet high by twelve feet wide by six inches thick, and it weighed 16,000 pounds. It was at a sculpture fabricator’s up in Connecticut.

I made an appointment with a crane company to meet me at Marcia’s Angelo Drive residence in Beverly Hills to determine what size crane we would need for the installation. Marcia showed us a location in the backyard where she wanted to place the sculpture. It would sit near her garage, close to the swimming pool, where a hedge directly behind the spot would backdrop the sculpture nicely. The crane estimator said we’d need a seventy-five-ton, self-propelled hydro crane. It would have to be set up on the street to lift the sculpture over the single-story garage and installed on a concrete pad Marcia’s contractor was pouring.

I arranged to have the piece trucked in from the East Coast, scheduled the crane, and gave Marcia a cost estimate. Unfortunately, the Los Angeles Olympic Games were scheduled to begin at the same time, so we couldn’t obtain the required permits to drive the truck and crane through LA into Beverly Hills. We postponed the installation date until after the games.

Five months later, I called my crane operator to remind him about the job. He said he would go back to look at Marcia’s house again. It sounded like a waste of time to me, but he insisted. The next morning, he called to report that the garage was two stories high, and we would need a much larger crane to lift the sculpture over it. I argued with him—we both knew the garage was only one story high. We’d seen it together. He must have gone to the wrong address. But he was adamant he had gone to the right place and said I should go take a look. He added that we’d now need additional tractor-trailers to deliver the crane and gave me a much higher estimate. I wasn’t sure Marcia would want to pay.

I went over to the house, and sure enough, Marcia had added a second room on top of the original garage during the Olympics. “Frank designed it for me,” she said when I arrived. I took that to mean Frank Gehry. My assumption was confirmed when she showed me the stairs that curved from the garden to the new upstairs room. They were clad in the galvanized sheet metal Gehry was beginning to use in his architecture and sat only a few feet from the concrete pad where the Serra sculpture, also curved, would rest. Marcia explained that Frank had seen a photo of the Serra and designed the stairs to “complement” the sculpture. But the clash of styles was going to look terrible.

I knew Serra wouldn’t be happy, but I hid my apprehension and tried to persuade Marcia that the sculpture should be relocated to another part of her garden. She rebuffed the suggestion as “nonsense.”

On a clear, chilly fall morning, the crane arrived. It was accompanied by truckloads of boom sections and the massive weights we would need to counterbalance the heaviness of the Serra to prevent the crane from tipping over. We set up barricades blocking each end of Angelo Drive. By the time the flatbed trailer carrying Serra’s sculpture pulled in, we had five large trucks parked up and down the street. The massive sculpture was too unstable to ride upright, so it was supported on a frame of steel girders at a 45-degree angle. This kept it braced, low and legal for driving across the United States.

Richard Serra showed up to supervise the unloading and set-up. He was in a good mood, joking with my employees and me while inspecting his sculpture as we discussed our installation plans. As the crew assembled the crane, Serra walked around the garage to the backyard. I followed a few minutes later and saw him standing on the sculpture pad with his hands stuffed into his pockets, staring unhappily at Frank Gehry’s staircase. He looked sullen and pissed off. It wasn’t a good sign.

I went back out to the street to watch the progress of the crane and noticed a line of Bentleys, Rolls Royces, and Mercedes sedans forming inside our street barricades. They were parking between the trucks and near the crane. Women dressed in afternoon cocktail attire got out of the cars and began walking through our work area to Marcia’s front door—completely oblivious to the dangers posed by the crane parts being hoisted overhead.

When the crane was almost set up, with its outriggers straddling the cribs of timbers that were keeping it level on the sloping street, I returned to the backyard. I saw that a party was in progress. Marcia had invited all of her friends to watch the installation. They sat at cloth-covered tables set with silverware and fine china. A butler dressed in tails was serving cocktails and finger sandwiches. The crowd swelled to around twenty women, boisterous and talking excitedly. Serra was still standing gloomily on his empty sculpture pad, looking down at his feet instead of the party on the other end of the lawn. Marcia had not invited him to meet her friends or join the party. She was pointedly ignoring him.

Trying to control the apprehension growing in my stomach, I returned to the street as the riggers were attaching “dogs”—large clamps that grip steel plates—to the top of the sculpture. The dogs dangled from steel cables attached to a spreader bar hanging from the crane hook. They were positioned so they would grip the sculpture a foot in from each end to keep it balanced while the crane lifted it. The clamps squeezed together like salad tongs, working on the principle that the heavier the weight, the greater the gripping pressure. Much like putting your fingers into one of those novelty Chinese finger traps. The harder you pull, the more difficult it is to get free.

Once the sculpture was safely airborne, the riggers and I rushed around the garage and into the backyard to wait for it to descend so we could guide it into position. The crane operator was on the opposite side of the house and couldn’t see us, so one of the riggers used a walkie-talkie to give him directions. I watched in awe as eight tons of steel gracefully swung high above a house filled with millions of dollars of paintings and sculptures.

The sculpture came overhead and slowly moved down until it was a few feet from the ground in front of the concrete pad. We were just about to tell the crane operator to stop lowering it so we could swing it into position when I heard Marcia shouting, “Yoo-hoo! Yoo-hoo! Richard! Oh, Richard! Could you turn the sculpture in the other direction so we can see how it looks?” The request was absurd because it could only face one way, but she was posturing in front of her friends, trying to show them that her purchase gave her power over the artist.

This was a huge miscalculation. Serra straightened up with a glare and yelled: “Lady, I’d rather shove it up your fat ass!”

Immediately chaos broke out. Marcia’s friends jumped up, knocking over chairs and spilling champagne glasses and china on the lawn. “How dare you talk to her that way!” they screamed at him. Serra stood his ground with his chin jutting forward and yelled back at the crowd.

The abruptness of the uproar distracted us, and the rigger forgot to radio the crane operator to stop letting out cable. I had turned my back on the sculpture and was looking toward Marcia when suddenly the whole thing fell over. The massive steel plate brushed my shirt sleeve on the way down. Had it come an inch or two closer, it could’ve cut off my arm or crushed me to death. It fell with the dogs still attached, suspending it at an angle about twenty-four inches off the grass, where it began violently yo-yo-ing up and down. I looked up. The crane boom was tilting dangerously over Marcia’s house and bouncing in rhythm with the steel.

My heart pounded, but I was completely calm. I ran—fast—underneath the wavering boom and out to the street. The crane was tilted at an angle with its outriggers sticking up in the air. It was barely balancing and within mere inches of toppling onto the house. The crane operator, in fear for his life, had jumped out and was standing a hundred feet down the street, visibly upset and wide-eyed. I yelled at him to get back in the crane and let out cable until the crane lowered itself back into position. Reluctantly, he climbed back into the cab and reset the crane while I raced back around the house where the hubbub was still going on. I got the attention of the riggers, and we lifted the sculpture and set it on the concrete pad in the correct orientation. In the heat of their fight, neither Marcia nor Serra noticed how close we had come to a complete disaster. If the crane had fallen, it would have destroyed the house and perhaps killed several of us, including Serra, who was standing on the pad underneath the boom.

Once the adrenalin began to subside, I could see that the sculpture was a wonderful piece. It was shaped in an arc, and when it sat on the pad, it tilted forward, balancing on the front points of the bottom corners with the rear of the curve elevated several inches off the concrete. The balance was so perfect you could shove a finger against it, and 16,000 pounds of steel would gently rock back and forth. It was by far the greatest Richard Serra I had ever seen. A passing breeze would set it in motion.

Finally, things quieted down, and in the midst of her friends, Marcia attempted to make peace. “Richard, would you help me break a bottle of Dom Perignon over your sculpture to christen it?”

Serra wasn’t in the mood. “I would rather break a bottle of beer on the goddamn thing,” he said. That brought the party to an abrupt ending, and the guests began heading to the exit.

Carried by a rush of exhilaration—We’d pulled off the save! The piece, the house, and all of us had come out unscathed!—I managed to persuade Richard to sit down with Marcia in an attempt to get them to talk. I felt like the adult trying to get two squabbling children to make up and act in a civilized manner. Marcia had her butler open the bottle of christening champagne and serve glasses to her and Richard. Still, the artist was having none of this rapprochement and sat in angry silence—his gaze shifting between his sculpture and the Frank Gehry staircase next to it.

The next morning Marcia telephoned me. “Bryan! Did you hear how that man talked to me? Did you hear what he said? I want you to get that sculpture out of my yard now! I am not going to look one more day at that thing! Get it out!”

I told her she should wait until things cooled down, that it was a fantastic piece, and she could still change her mind. Removing it was going to cost just as much as installing it, I added, hoping that would slow her down. “I don’t care!” she said. “Get it out of my yard!” She hung up. A week later, we went back to take the Serra away.

Twenty years after those events, I finally developed several rolls of black and white film that one of my employees had taken during the installation. There in the midst of Marcia’s coiffed friends, stood Frank Gehry. I hadn’t noticed him that day. He was laughing his head off.

I got more insight into what was going on when the New Yorker ran a long article about Richard Serra in 2002. Calvin Tomkins interviewed both Gehry and Serra. He described their competitive relationship and the sculptor’s assertion that architects are not artists. The piece also delved into the Marcia Weisman incident from Gehry’s viewpoint. The evening following the near disaster, Gehry called Serra and suggested he send Marcia a dozen roses to make amends. Several hours later, a dozen roses were instead delivered to Gehry with the note: “Shove these up your ass!”

I could see how Frank Gehry might have enjoyed goading Richard Serra with the curved staircase—but what stayed with me was how they were so absorbed in the theatrics of their one-upmanship that neither of them noticed when it nearly turned fatal.

Gehry became a client of mine over the following decades, and as his career grew, we crated, shipped, and stored hundreds of his models. In the early days, he called me directly to discuss the work he wanted done. But as his reputation grew, the contacts were always through his employees. One morning, I was waiting at the reception desk in his architecture offices in Santa Monica when he walked in, ignoring me as he strode past. “Good morning, Frank,” I said politely. But his shoulders stiffened as if he were deeply offended, and without acknowledging me, turned his back and walked away. Would he have cared if I had died because of his curved staircase?

But Serra was different. A rigger had been killed in the 1970s when one of Serra’s lead sculptures fell on him at the Walker Art Museum. It was a tragedy that deeply affected Serra, and I believe he would have cared a lot. I never had an opportunity to work with him again directly, but I’ve moved and installed his sculptures on other occasions—always very cautiously.